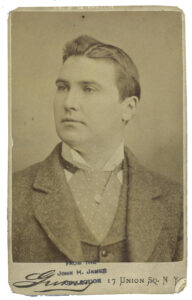

Edward Arnott (1843-1885) was one of the six founders of The Lambs in December 1874. His acting career began in England and he was a member of Wallack’s Theatre upon his arrival in New York. He toured the U.S. extensively with various productions. The Times said he was a “tall, stoutly-built man, with handsome features and a rich voice.” Arnott played comedy and drama, and could be counted on for Shakespearean roles and what passed for musicals in the 1870s. Arnott’s professional career was cut short by acute alcoholism.

Edward Arnott (1843-1885) was one of the six founders of The Lambs in December 1874. His acting career began in England and he was a member of Wallack’s Theatre upon his arrival in New York. He toured the U.S. extensively with various productions. The Times said he was a “tall, stoutly-built man, with handsome features and a rich voice.” Arnott played comedy and drama, and could be counted on for Shakespearean roles and what passed for musicals in the 1870s. Arnott’s professional career was cut short by acute alcoholism.

He was born Edward Alexander Job in Quebec, Canada, on March 5, 1843, to Samuel Job, a native of Warwickshire, England, and Mary Job, of Roscommon, Ireland. His father was a groom. As a boy the family moved to England and settled in Birmingham. When he was 14, he lied about his age to join the British Army, saying he was 18. On March 1, 1858, he enlisted with the 15th (The King’s) Hussars at Aldershot, a cavalry regiment. He said he was a clerk. Military records state young Edward was 5’6” with hazel eyes, dark brown hair, and a “fresh complexion.”

Edward did not have much of a military career, but he did travel around: Stationed at Norwich (1858), Hampton Court Palace, Surrey (1859), Dublin (1860). He left the Hussars on April 7, 1860, ending his military service for Queen Victoria. He was 17 years old.

Of his army days, there is a stray reference to it. He told a reporter, who shared it with the American Gentlemen’s Newspaper around 1875: “Edward Arnott, then a mere boy, was at the first storming of the Redan in the Crimea, and bears on his right arm a sword wound received in the Second Square of the Redan.” [A major battle during the Crimean War, fought between British forces against Russia on June 6-9, 1855, as a part of the Siege of Sevastopol. Arnott would have been 12 years old]. In America, Arnott would often brag he’d been an officer in the British Army.

What happened to push him into acting isn’t clear. He changed his name from Job to Arnott. He lived in Bristol for a time from 1866-1868 and turned up acting at the Theatre Royal, Bristol (1868) and Theatre Royal, Oxford (1869). His first appearance in London was as Claude Melnotte in The Lady of Lyons in which he supported Mrs. Scott-Siddons (Mary Frances Scott-Siddons) at the Haymarket Theatre. He later got parts there (1872-1873) in The Irish Lion. Possibly his last role in London was playing George Washington in The Manager in Love (1873).

Around this time, he met and (possibly) married his first wife, Emma Mills. She gave birth to twins, Marie and William Arnott, on March 15, 1874. He was not around because he’d left the country. On October 17, 1873, he boarded a steamer, the RMS Cuba, bound from Liverpool to New York. Arnott abandoned his wife and children and never returned to England.

Arnott arrived in New York in late October 1873. No time was wasted in securing work; possibly using connections with associates from London, such as Irish playwright Dion Boucicault, who is believed to have recruited him. He made his American debut at Wallack’s Theatre, at 13th Street and Broadway, on Nov. 10, 1873, as Angus McAllister in Ours. He was 30 years old.

Arnott did not spend much time in New York after his emigration. He went West almost immediately, touring with a road company to California. He was soon making headlines, and not for his acting.

The San Francisco “Figaro” of Aug. 27, 1874, says: “Dispatches from Sacramento state that Edward Arnott, the leading man of the dramatic company now playing there, and little Sam Genese, the stage manager of the same company, went out early yesterday morning to settle a personal difficulty by fighting a duel…Arnott knew before going to the grounds that there were to be no bullets in the pistols, and on that condition, he agreed to fight, but Genese was earnest in his intentions.” After three shots were fired, “Capt. Stevens of the police force put in a pre-arranged appearance, and arrested all parties, who were soon after released…The difficulty is said to have been concerning one of Barnum’s female jockeys (possibly his mistress, Emma Elizabeth Champness, who was reported to be a circus equestrienne at the Hippodrome), who is reported to have accompanied Mr. Arnott to the Pacific slope.”

Arnott returned East within a matter of weeks, and went back to work at Wallack’s Theatre.

The Shaughraun was written by Dion Boucicault, also a charter member of The Lambs. Many of the cast would be founders and early members of the Club. It debuted Nov. 14, 1874, at Wallack’s Theatre and continued a successful run until the following April. Arnott was the original Corry Kinchella. It was in December 1874 that The Lambs was created from these Shaughraun actors. Among Arnott in that run were some of the very early members of The Lambs: Boucicault, Harry Beckett (2nd Shepherd), John Gilbert, E. M. Holland (6th Shepherd), and Henry James Montague (1st Shepherd). When the run ended, Arnott left town, and booked a stay in Chicago. It was a city he would return to.

Arnott received some of the highest praise of his career in February 1876 from the Brooklyn Eagle for his part in Queen and Woman, a Victor Hugo story that had been adapted by another member of The Lambs, Steele MacKaye, at the Brooklyn Theatre. “Mr. Edward Arnott has developed powers even his friends had little suspected. His singing of the serenade in the first act was exquisite, and the morceau was vociferously redemanded. Mr. Arnott, indeed, shone out as the gallant figure of the play.”

Arnott was loaned by J. Lester Wallack in April 1877 to appear in Anne Boleyn at the Eagle Theatre in New York for manager Josh Hart.

The next of Arnott’s public scandals occurred in 1877. He was sued for divorce by an English actress, a fellow member of Wallack’s stock company. She went by many names: Emma Elizabeth Champness, Emma Elizabeth Arnott, Ethel Thornton, Rose Allayne. When Arnott met her in June 1874, she was Rose Lyle and the mistress of another actor, he claimed. The Oswego (NY) Palladium reports: “Both are actors at Wallack’s. Rose alleges private marriage. Edward denies that there was any, and says he has a wife and family without Rose. The parties have been playing in False Shame on the stage, and their friends are surprised at their appearances in real shame off the stage.”

She sued him for divorce and the couple squared off in November 1877 in New York Superior Court. The lawsuit was splashed over all of the city newspapers, and the salacious details reported nationally. Rose claimed Edward met her in various downtown private homes and boarding houses; he put a ring on her finger, saying, “Now you are my dear little wife;” and she responded, “I will try to be a good little woman to you, Ned,” reported the Times.

Later, Rose pushed her husband for a church wedding with a clergyman. Arnott erupted, saying, “If I marry you in church, you could not be more my wife than the law now makes you.” He didn’t tell her about his family in England; instead, he took her to San Francisco for acting work. While out West he beat her, which sent her packing, she said. He followed her back to Manhattan and they reconciled. They had a baby who did not have a long or happy life; Arnott said in court that on one occasion when the child was several weeks old, he found Rose in bed, “dead drunk beside the child.” Arnott said he had no money to pay for his child’s funeral. She sued him for absolute divorce, claiming he had been with other women. She sought $100 a month alimony plus $500 attorney’s fees. When the case was heard, Arnott confessed to having a family in England and that Rose was his mistress. Arnott was asked to provide proof of his first marriage, which he could not comply with. His defense hinged on saying he was married, Rose knew that fact, and she agreed to be his traveling companion-mistress.

“In this city, last week,” the New York Clipper reported Dec. 1, 1877, “the English actress who for the past two or three seasons has played at Wallack’s Theatre under the pseudonym of Miss Ethel Thornton brought suit for divorce from Edward Arnott, an English actor, and of the same theatre. She alleges brutality…He makes a startling admission under oath but denies that plaintiff ever became his wife. She claims that she was married to him in this city, in June 1874 [under] the laws of the State of New York, although the religious ceremony she asked for was dispensed with in deference to his logic. She furthermore affirms that she accompanied him to San Francisco as his wife, and continued to live with him as such until she made the painful discovery of this [fecklessness]. By way of proof that he could not, or at least ought not to, have married Miss Thornton, he swears that he has a wife and two children in England. And we are inclined to think that he is right. It is at least a “probable certainty” that on March 15, 1874, Mrs. Edward Arnott, in England, gave birth to twins—a boy and a girl. Miss Thornton swears that she was not aware that Mr. A. had a wife in England; and yet The Clipper in April of 1874, published that item about the twins for the guidance of all [theatrical] maidens…”

Arnott escaped any consequences when a few weeks later, the judge ruled: “In deciding this motion I do not express an opinion as to the merits of the controversy, but on the facts presented as to the ceremony testified to by plaintiff; I must exercise my discretion by denying the present application.

The following month, in January 1878, Arnott was fired by J. Lester Wallack from the eponymous stock company he had been a member of since he landed in America five years before. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle ominously reported, “Edward Arnott has left the Wallack Company, for reasons deemed sufficiently strong by the careful management of that house.”

Six months later, Arnott escaped punishment in June 1878, when he was accused of beating a Manhattan reporter with his walking stick. He was arrested and charged with assault. A grand jury dismissed the complaint. The actor returned to a railroad station and resumed a touring schedule.

His name and another marriage made the news less than two years later. The New York Clipper broke the wedding news. On Oct. 20, 1879, in Louisville, Kentucky, “Edward P. Beaufort, professionally known as Edward Arnott, was married…to Minnie L. Morgan, a Kentucky Belle.” [The Clipper later reported the new pseudonym he was using was Edward Plantagenet Beaufort, cleverly appropriating the names of British aristocrats as a new identity]. The Baptist wedding was held at the Broadway Church in Louisville. At the time Arnott was traveling between Cincinnati and Louisville. This was the union that would bring him another son, and continue his practice of bigamy. A report said Edward and Minnie had been acquainted just six weeks before marrying.

Arnott and his wife were in Chicago for the birth of their son, Charles Edward Arnott, on October 5, 1880. Following his familiar pattern, the actor abandoned his wife and child. [His son would go on to have a Horatio Alger-type life and rise to become president of Socony-Vacuum Oil, today called Mobil].

In October 1880, Arnott was back in Manhattan at the Bijou Theatre with two brother Lambs, Dion Boucicault and Charles A. Stevenson, both charter members. Boucicault had adapted a French play into The Snow Flower for the actors, with a cast of several actresses, led by a leading lady of the age, Kate Claxton. The Herald critic said, “Mr. Edward Arnott’s Bernard was somewhat stagey in the first act, but like good wine, he seemed to be improved by age, and as the decrepit old man he was unquestionably good.”

In 1881-1883 Arnott was on the road, traveling with popular star Kate Claxton in The Two Orphans. He went West in June 1881 to perform with the cast in Sacramento, California, and South to Memphis in April 1883. When the company returned to the East Coast; it played in Brooklyn at the Novelty Theatre. Arnott spent countless hours on trains; he spent the majority of his 11 years in America crisscrossing it by rail and rooming in hotels.

On October 14, 1883, one of the most respected newspapers in the country, the New York Herald, reported: “Mrs. Edward Arnott, wife of the actor of that name, charges her husband with desertion. He is said to have fled from Philadelphia, where he was playing an engagement… [By telegraph to the Herald, from Philadelphia, Oct. 13] “The second wife of the actor Edward Arnott has for months past made all sorts of charges against him, and he has denied the charges time after time. To-day she appeared with her three-year-old baby before Magistrate Lennon, and swore out a warrant charging Arnott with desertion. Mrs. Arnott, a slender, pretty brunette, created a sensation last year by denouncing her husband at the theater and having a warrant issued for his arrest for non-support. He patched the matter up and escaped from the city. Arnott came to Philadelphia three days ago to rehearse the part of Edmund to Mr. Sheridan’s King Lear. His second wife, who was a Miss [Morgan], had lost sight of him for some time. She hunted him up and found him at rehearsal yesterday. He wanted to know what had become of their child. She refused to tell. The husband and wife quarreled, and she resolved to have him arrested for desertion. Someone told Arnott that a warrant was out for his arrest, and he threw up his engagement with Fleischman & Hall and left the city. His place was filled by an actor named Brent. The constable who had the warrant for Arnott scoured the city in search of him yesterday, and Mrs. Arnott, with her child, visited a number of theaters in the hope of finding her husband.”

The Memphis Commercial Appeal published an interview with Arnott on Nov. 4, 1883, where he filled in some rich biographical details: “I am not the man to be frightened by a poor house or a grasping manager,” says Edward Arnott, the tragedian, in a voice like the melancholy Dane’s, “but when a man’s wife turns traitor then I give in. Four years ago, I married Minnie Morgan. I loved her, worked for her and did all a man could do. We would to-day have been living in happiness but for her father and mother. Her parents have been the evil genie of my fireside. They taught the girl to look upon me with the utmost disfavor. I was making money, and bought her dresses, hats, silks, diamonds, everything that money could secure. A child was born and died; then another, a bright little boy, came into the family circle. His name is Charlie. But the boy did not make my wife love me any better. Her parents followed me from state to state, wringing money from me. They hung upon me like a shadow until they darkened all my life. Finally, my wife left me and took my boy away; but if there be any power in money, or if the eternal vigilance and work of an agonized father can bring that boy back, I will have him. Two weeks ago,” he continued, “I fell in a faint in the street, and have been sick ever since. My wife and child are with my mother-in-law now in Philadelphia. I was in Cincinnati. They followed me here. I was in Chicago, and there they pursued me, always haunting me like an evil dream. But I love the girl still. I would buy her the dresses again; yes, and the diamonds too, were she away from her parents.”

“Edward,” the newspaper concluded, “notwithstanding this episode, continues to play tragedy, and since the occurrence is said to be especially strong as Othello.”

The events leading up to Arnott’s final downward slide took a dark turn in the fall of 1883, when he was 40 years old. He was back in Manhattan and drinking heavily. He brought a handgun to confront John Stevens, the actor, author, and manager of the Windsor Theatre, a playhouse on the Bowery. Stevens was in his office above the theater.

He told the New-York Daily Tribune on November 23: “An actor named Ned Arnott, whom I have known for some years, came to me about two weeks ago and begged me to give him an engagement. I knew he was given to drinking to excess and so had to refuse him. He begged and prayed so hard, however, that I gave him a chance on his solemn promise to refrain from drink altogether. I lent him $5 when he first came, and on Saturday last when I handed him his part, I gave him at the same time a check for $50. On Tuesday he appeared at rehearsal and I noticed he was strange in his behavior. He told me confidentially that he had been pursued by some blackmailers and that there were two in the theater at that moment.” Arnott was removed from the theater, and then checked into a hotel across the street, bringing a loaded gun to his room. Stevens said the hotel staff reported Arnott to the police after he made threats to murder Stevens, and his room was raided and his gun confiscated. Arnott then showed up at other theaters, telling actors and managers that he was being pursued, and he was hearing voices through his room’s keyhole. The Tribune wrote, “He has been drinking hard lately and his acquaintances suppose his sudden reformation–he signed the pledge last Saturday–may have finally overturned his weakened brain.”

On Nov. 27, 1883, the Tribune reported: “Edward Arnott, the insane actor who recently attempted to shoot Mr. Stevens… was recognized about 6 O’clock yesterday evening, standing on Broadway in front of the Star Theatre by a friend, who is a ticket speculator. Arnott was evidently suffering from delirium tremens. His friend took him to the Mercer Street Police Station, and Sergeant Douglas, after an examination had been made by Doctors Dorn and Ambulance Surgeon Larkin, of St. Vincent’s Hospital, had him sent to the building for the insane at Bellevue Hospital.”

The following day, Truth, a daily newspaper, printed a brief interview with the actor, who they claimed had visited their offices at 142 Nassau Street: “The actor, of whom the papers have said much lately, called on Truth last evening. He was looking remarkably well, and then undoubtedly like the man in the Scriptures, ‘clothed in his own mind.’ ‘The police reports of my trouble,’ he said, ‘have been very much exaggerated. The case was not as bad as it was made out to be. I know that my system has been run down somewhat, and I have concluded to go in retreat for a couple of weeks. I know I need to recuperate, so I will remain in St. Vincent’s Hospital for a while. When I leave there, I shall join a company, and the people can then see that my usefulness has not been impaired.’ “As he was leaving the actor remarked:” ‘I really never knew how many or staunch were my friends until this trouble, when they all treated me most kindly.”

On Dec. 1, 1883, the New-York Daily Tribune reported: “Edward Arnott, the actor, is still in the Insane Ward at Bellevue Hospital under Dr. Wildman’s care. He has been rather violent but it is expected that in a week or two he will be discharged cured.”

Arnott was released from Bellevue, and true to his word, he signed a contract to join a road company. He went back to an old favorite, The Two Orphans, but without its star, Kate Claxton. He was with the company as it toured the Midwest through the summer of 1884. Arnott would never return to New York.

In early 1885 he was spending the winter in Chicago while onstage at the Halsted Street Opera House, on the corner of Halsted and Harrison streets. It was a third-class operation, known for stock companies and minstrel shows, hugely popular in the era. He had attempted to lease a separate theater but the plans fizzled. Arnott was living nearby with actress Belle O’Brien; she was billed as Belle Arnott. The couple told everyone that they were married. His last appearance onstage was in Trust at the playhouse.

In February–unable to pay the month’s rent, lacking money, food, and coal–they were ordered to leave their lodgings. He unsuccessfully attempted to slash his wrists. On February 5, 1885, Arnott committed suicide by slitting his throat with a razor. He was 41 years old. Arnott was interred in Graceland Cemetery on Chicago’s North Side. The Actors Fund (just three years old and co-founded by Arnott’s mentor, J. Lester Wallack) stepped in to cover the burial costs. However, Arnott lies today in an unmarked grave.

Of the obituaries, there were few. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle recalled, “The rapid downward course of a former leading man of Wallack’s Theatre…he had been dissipated for several years and had gradually gone down to the bottom of his profession.” A scrap reprinted in the Jamestown (NY) Evening Journal said that after The Shaughraun, “He never did anything else on the stage worth mention, and his monetary affairs and social relations were generally under a cloud.”

The American Gentlemen’s Newspaper wrote: “Edward Arnott, a member of the dramatic profession, committed suicide in this city, Feb. 5th. His last appearance was at the Halsted Street Opera House, Jan. 25. A Canadian by birth, and forty years of age. He was at different times connected with several traveling companies and was a bright and brilliant member of the fraternity.”

—Researched and written by Lamb Kevin C. Fitzpatrick, Club Historian. Thanks to Jo Bailey for family genealogical research.