DeWolf Hopper (30 March 1858 – 24 September 1935) was a New York actor, comedian, singer, and producer. A star of musical theater, he made the baseball poem “Casey at the Bat” famous by performing it 12,000 times. He was elected to The Lambs in 1887, served as Shepherd 1900-02, and is an Immortal Lamb.

DeWolf Hopper (30 March 1858 – 24 September 1935) was a New York actor, comedian, singer, and producer. A star of musical theater, he made the baseball poem “Casey at the Bat” famous by performing it 12,000 times. He was elected to The Lambs in 1887, served as Shepherd 1900-02, and is an Immortal Lamb.

To welcome in the exciting new century, a more colorful personality could not have been found for Shepherd of The Lambs than comic opera star DeWolf Hopper, elected in October 1900. He had a three-octave voice that thrilled audiences and a three-octave sex life that thrilled the ladies. “The Wolf Hopper” was a delightful name. Like Henry XIII, he married six times, but unlike the fearsome English monarch, he remained friends with all of his wives. This fact alone must place him in the pantheon of the stage’s most remarkable men. The fame of the merry Hopper rests on his 50 years as a star in comic operas and operettas, and his electrifying recitations of “Casey at the Bat.”

Born William D’Wolf Hopper on 30 March 1858, he was the only child of a straight-laced Quaker family in New York City. Satyrs spring alike within the households of the morally lax and the proper, much to the annoyance of the latter. His grandfather was Isaac Tatem Hopper, the Quaker philanthropist and abolitionist; his father was a well-connected lawyer; his mother was a high-church Episcopalian D’Wolf of Rhode Island. The actor wrote, “I was born to the stage, although, paradoxically both my father and mother came from stock that never set foot in a theatre.” They considered the stage the vestibule to Hades.

His father died when he was a boy but left the family well off. As a young student at J. H. Morse’s School in Midtown, DeWolf showed a talent for the stage, and his recitations from Shakespeare entertained the Hoppers’ circle of friends in their parlor. He lapped up the applause. His school performance at age 15 in Ralph Roister Doister (the earliest extant English comedy) seems to have clinched his desire to become an actor.

This did not sit well with mother. As William came of age, she maneuvered for him to study law at Harvard. After one of the briefest educations on record there he quit, declared that he would go on the stage at once, dropped William, and changed D’Wolf to DeWolf for the marquee value. His friends called him Will or Wolfie. Worn down by his mother’s pleadings, he began to read law in the offices of the illustrious Joseph H. Choate, his godfather and later U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James. Choate, who had been a close friend of his late father, didn’t take long to decide that the restless young man would never become an attorney, consulted with his mother, and DeWolf began acting. His mother, to whom he was inordinately attached, desired for him to pursue tragedy or grand opera, which she considered more dignified, and he studied with an Italian coach, a move that ultimately helped his career.

Playwright Augustus Thomas, a Lambs’ stalwart, thought he was right for tragedy and took him to Charles Frohman, the most important manager of the day. He said to Frohman,

“Charley,” he began, “here is your chance to do a big thing for the theater. Hopper’s talents are being thrown away in comedy. He has the frame and the voice for tragedy. Heroics demand the heroic, but who have we among our tragedians that fills the bill? Look at Thomas W. Keen and E.H. Sothern! Splendid actors, I grant you, but neither with the robust voice or stature. Here is Will, a man intended by Nature for the heroic, and the stage is using him as a clown. You are the manager to rectify this blunder, to give our stage a tragedian who looks the part.”

Frohman listened politely, and after a while spoke. “What you say is substantially true, no doubt, Gus, with the important exception that it can’t be done. Will has all the physical attributes of tragedy and he is a first-rate actor, but his public expects him to be funny and would resent his being anything else. They have labeled him as comic and comic he must be.”

Hopper accepted the verdict and with it its lifelong sentence. His autobiography was called Once A Clown, Always A Clown.

Baseball in 1888 was truly the Great American Pastime. In the summer of that year Hopper took part in a benefit for the New York Giants, of which he was a passionate fan–his passions were not confined to the female sex. At Wallack’s Theatre, at the time located at Broadway and 30th Street, where he was a member of the company, he recited for the first time the then-unknown dramatic poem “Casey at the Bat” by newspaper writer Ernest L. Thayer. With the theatrics of a master, his huge voice bombed the concluding lines about the great mythical baseball player:

Oh, somewhere in this favored land

the sun is shining bright;

The band is playing somewhere, and

somewhere hearts are light,

And somewhere men are laughing,

and somewhere children shout;

But there is no joy in Mudville—

mighty Casey has struck out.

Hopper brought the house down. The audience included members of the Giants and the Chicago White Sox in box seats. The theatergoers went wild and “Casey” became an instant sensation. A statistician estimated that by his 76th birthday Hopper had recited “Casey at the Bat” roughly 12,347 times. The actor quipped that he expected to be repeating the lines on Resurrection morning, and once said, “l have recited it at dinners, luncheons, tea, banquets, and all other places where two or more persons were gathered.”

With comically long legs and an expertly trained, fine basso profundo voice, he became one of the most popular performers in comic opera. He gained star billing in Castles in the Air (1890), secured his position as the Regent of Siam in Wang (1891), in John Philip Sousa’s El Capitan (1896) in both New York and in London, and in Happyland (1906).

His mother did live long enough to see her son in one minor success in a classical role–in the Lambs Gambol of 1909 he recited Anthony’s oration over the body of Caesar.

During mid-career he concentrated on Gilbert and Sullivan, playing Ko Ko in The Mikado more than 1,000 times. When he played the sheriff in Lamb Reginald De Koven’s Robin Hood, a critic wrote, “In Mr. Hopper’s hands he remains a thoroughly entertaining creation and a highlight of last night’s performance of good old Robin Hood.” He was a headliner on the opening night bill of Radio City Music Hall, “the theater of magnificent distances,” when in 1932 it opened as a Vaudeville house.

At six foot three, he stood head and shoulders over the acting companies with him on stage. He didn’t have a hair on his body, having lost all his hair, including his eyelashes, from typhoid fever in his teens. The hair one sees in photographs is a “rug.” The hairless, lanky Hopper, with unfortunate, fleshy lips, had never, even in youth, been picture-book handsome, yet women lusted after him, and even after their divorces all of his wives spoke of him fondly.

The six wives of the DeWolf Hopper:

Wife Number 1 was Ella Gardner, a cousin on his mother’s side.

Wife Number 2 was Ida Mosher, an opera singer by whom he had a son, John, called Jack, who became an official with Chemical Bank and Trust.

Wife Number 3 was Edna Wallace Hopper, called “the eternal flapper,” whom he met in 1893 while she was appearing on Broadway in The Girl I Left Behind Me.

Wife Number 4 was Nella Bergen, daughter of a Brooklyn police captain. She was an opera singer.

Wife Number 5, Elda Furry, a butcher’s daughter, married Hopper in 1913. It was his magnificent voice that won her over. “It was like some great church organ,” she said. “This giant of a man was all music and traded joyously on his voice. It could make you laugh, it could make you cry, and it didn’t matter which–you just knew it was wonderful.” They had a son, William, who became an actor. The names of Hopper’s first wives were “pitched in the same key,” so he changed hers to Hedda. At Hopper’s fifth divorce trial, the exasperated New York judge granted his wife’s divorce, alimony, and custody of their son. He forbade the defendant “from marrying any other person during the lifetime of the plaintiff, except with the express permission of the court.” So for his sixth wedding Hopper went to Connecticut. After a middling career as an actress, Hedda went on to become a powerful and feared Hollywood gossip columnist for 50 years.

Wife Number 6 was Lillian Glaser. When DeWolf married her in 1925 he was 67. She was 29, a singer, and the widow of a dentist.

The day before his 76th birthday in March 1934, he sat for an interview with a reporter from the Tribune in his apartment at the Victoria Hotel. The shabby Victoria was at Broadway and 27th Street. It was not in the heart of the Theatre District, but it was budget priced; Hopper had been hit hard in the Depression. Like many actors, Hopper’s night was his day. At 3:00 PM he emerged from his hotel room and sat down for a breakfast of grapefruit, egg boiled 2 1/2 minutes, toast, marmalade, and coffee. The reporter noted that he lived at The Lambs and slept at the Victoria.

“Oh what a night I had,” began Hopper. Due to his notoriety he felt he should explain. “Nothing romantic, understand, but a big night just the same.”

He then grew more solemn. “At my age, I’m beginning to long for immortality”, he said. “I crave immortality if for no other reason then to see my dear mother again. Religion to me is a beautiful poem. I am an agnostic. I am not an atheist. I would not argue against the beliefs of anyone. I have not the ego of those who would believe one thing and another.”

A year later he gave a reporter his opinion of the modern woman. “She wears 90% less clothing than she used to, but takes up just as many hooks in the closet.”

On the afternoon of September 23, 1935, he was in Kansas City for a radio broadcast. Although visibly weak and unwell, he refused to cancel. The announcer said later that Hopper “took the microphone and with not a blur or quaver. He went through the program like a red-ball freight. He was at his best.”

Against his protest, he was taken to a hospital. At 11:00 PM, sitting up in bed, smoking a pipe, and studying baseball scores in the newspaper, he shooed a doctor away. “See you tomorrow, doc,” he said. “I never sleep until 3:00 AM anyway. Run along while I see what the Cards did.”

He died of heart failure at 6:30 AM the next morning. He was 77 years old.

The Little Church Around the Corner was packed for a heart-warming funeral; one-thousand more stood outside. Twenty-five patrolmen were assigned to manage the crowd. Beside his sixth wife was his third, Edna Wallace, his sons John, a banker, and William Jr., who would become an actor on television. A choir from The Players, of which Hopper was also a member, sang some proper hymns. The impish Lambs’ choir sang King of Love, My Shepherd Is.

DeWolf Hopper is buried in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, next to his parents, but not with any of his spouses. For his contributions to The Lambs he was named an Immortal Lamb.

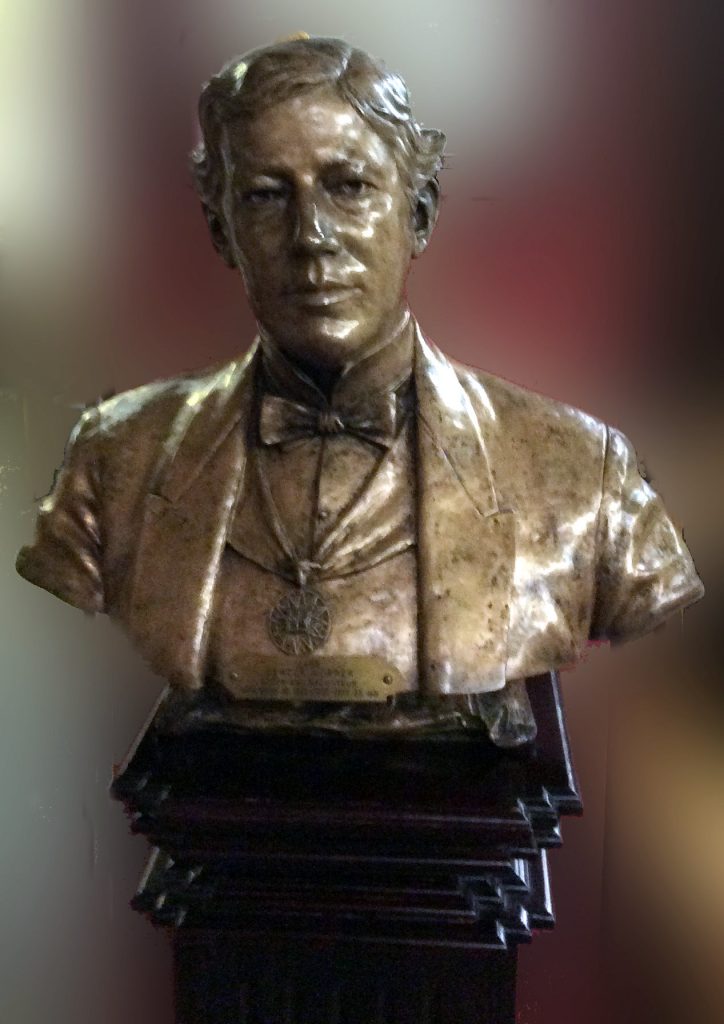

Today Hopper is the only former Shepherd who has a bust instead of an oil painting in the Lambs’ clubhouse. A copy was donated by The Lambs to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, where scores of “Casey” and “Mudville” artifacts reside in its collection.

Adapted from the research and writing of Lambs’ historian Lewis J. Hardee, Jr. Additional research by librarian Kevin C. Fitzpatrick.