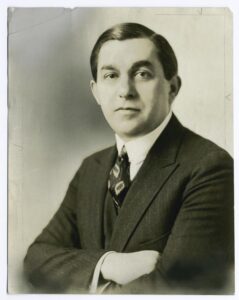

John L. Golden (27 June 1874-17 June 1955) worked in every single creative role in theatre and was a tireless champion of Broadway. He rose from writing novelty songs to producing major hits to become one of the most popular of any Lambs’ member before World War II. He was a producer admired and loved by actors. The Actors Strike of 1919 was a turbulent time for him as a manager, but he weathered it. “Poor Butterfly” is perhaps the best known of the songs he wrote during his early stage career. For years he was central to The Lambs, serving as Shepherd 1942-1945. He gave generously to the Club during his lifetime and also left a sizable fund in his will. He was named an Immortal Lamb.

John L. Golden (27 June 1874-17 June 1955) worked in every single creative role in theatre and was a tireless champion of Broadway. He rose from writing novelty songs to producing major hits to become one of the most popular of any Lambs’ member before World War II. He was a producer admired and loved by actors. The Actors Strike of 1919 was a turbulent time for him as a manager, but he weathered it. “Poor Butterfly” is perhaps the best known of the songs he wrote during his early stage career. For years he was central to The Lambs, serving as Shepherd 1942-1945. He gave generously to the Club during his lifetime and also left a sizable fund in his will. He was named an Immortal Lamb.

When Golden was elected Shepherd in October 1942 he had been a Lamb for 50 years, after his election as a member in 1893. His achievements are so numerous they hardly seem the work of a single man. He was an actor, newspaper writer, U.S. Army officer, lyricist, dramatist, songwriter, playwright, producer, civic leader, and philanthropist. The theater was his life; he named his autobiography Stage Struck John Golden. Today the John Golden Theatre, built in 1927, on West 45th Street, preserves his name.

Born in New York City on 27 June 1874, he was raised in Wauseon, Ohio, a small town west of Toledo, where his English-born father, a school teacher, also ran a small summer hotel and was later leader of a local band. As a kid he began selling verses to the newspapers and then lyrics for Broadway musicals. He studied composition under Walter Damrosch and contributed songs to Broadway shows. Most of these were short-lived and soon forgotten: Miss Printt (1900) for which he wrote both lyrics and music lasted less than a month. But made a star of Marie Dressler.

Golden gained a reputation as a sound craftsman and fix-it man. For a decade he turned out lyrics for a string of extravaganzas at the Hippodrome Theatre, rubbing shoulders with anyone and everyone connected to the biggest theater in Broadway history. Hip-Hip-Hooray (1915) and The Big Show (1916) each ran for 425 performances.

In 1914 he joined the rising producer, an immortal Lamb, Winchell Smith, and two years later the team scored a hit with Turn to the Right. Four years later Lightnin’ opened to break records as the longest-running play of its time. During his career, Golden produced more than 100 plays on Broadway, including The Male Animal in 1953.

He died of a heart attack in his sleep at his home in Bayside, Queens, on 27 June 1955, a few days shy of his 81st birthday. At his memorial service at the Colonial Reformed Church in Bayside, Eleanor Roosevelt was one of the guests who joined scores of Lambs. He has a vault in Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum in Hartsdale, New York.

John Golden’s legacy made him an Immortal Lamb: He left his Queens estate to the city, today it is 17-acre John Golden Park. A playwrighting scholarship is awarded annually by Hunter College.

From the Lambs’ Script January-February 1945 issue

City born, farmer boy, actor, newspaper writer, rhymester, dramatist, songwriter, playwright, and producer all went into the making of a Shepherd.

The late, beloved Lamb, Irvin S. Cobb, wrote,

John Golden‘s is the salty, savory, whimsical tale of a boy who was, to begin with, an Oliver Optic sort of kid–but with none of the namby-pamby traits of the typical Oliver Optic hero–and who chugged ahead, generating his own steam as he went, and he grew to be the man the American theatrical world likes and admires–a master showman, a wise and witty companion, a generous giver of his time and money to worthy causes and less worthy individuals; a patriotic, clean-minded, clean-living citizen, in short, as Broadway would put it, a regular guy.

Our hero came to being on June 27, 1874, nine years after the close of the Civil War. His father, Joel, came here as a boy on a sailing vessel from Manchester, England. Joel brought with him an assortment of abilities in the way of trade and professional expertness as a musician. When they settled in Wauseon, Ohio, Joel became the leader of the local band. Two $64 words, according to the Shepherd, best describe his father: “ubiquitous” and “peripatetic.”

John’s first job when he reached New York was with the well-known Tammany Hall building contractors, Horgan & Slattery. After a year or so, the boss, Mr. Horgan, discovered hundreds of reams of the firm’s stationery were missing. Later, he found these were being used by young Golden on which to write plays. (John Golden still has a number of these Horgan-Slattery dramas.) Horgan, being eager to help Mr. Golden, not only retire from his employ but to further his theatrical ambitions, sent young Golden to his father-in-law, owner of Poole’s Theatre, with a letter which resulted in our Shepherd working there in a job that had various responsibilities ranging from cleaning out the washrooms to taking tickets.

On some nights, it is a fact that he not only took tickets at the door but appeared on the stage as a super. He bragged about his confidence as a super to such an extent that he graduated to Nilo’s Garden where they paid ten cents a night more for his services than they had at Poole’s Theatre. But, at least, he had entered the theatre. A well-known manager of that day, Walter Sanford, saw Golden and gave him his first New York City job, a small bit, as a matter of fact, three small bits–in those days they not only doubled, they trebled—in a play by author Henry Guy Carlton. It was called Ye Early Trouble, and was one of the very first productions done at Proctor’s 23rd Street Theatre. He followed this with the juvenile lead in A Night’s Frolic by Augustus Thomas, and two seasons of Shakespearean repertory.

Then came a period in his life when he began to write rhymes and to sell them to the newspapers. Later, he began to write songs, the seedlings of several hundred since produced–many of national popularity. Somehow, within the day’s limit of 24 hours, and the demands of his job, he attended college. He became a member of the New York University Class of 1894. Years later, Chancellor Brown of NYU publicly presented Mr. Golden with a beautiful engraved silver cup as an acknowledgment of his work in organizing the drama department of the University.

He wrote the lyrics and music for Marie Dressler‘s first play called Miss Printt, which was produced at Hammerstein‘s Theatre. Golden followed this with a string of musical play successes, writing both the lyrics and music. In Vaudeville he wrote The Clock Shop, The Vanishing Princess, River of Souls, and other one-acters. Then comedies, with Kenyon Nicholson: Eva the Fifth, with Hugh Strange, After Tomorrow, with Vicki Baum, The Divine Drudge.

Enough of the story of the Shepherd’s life and his past history. His record as a producer from Turn to the Right down–or up if you like–is Three Is A Family, covering the production of more than 100 plays, is theatrical history and too well-known to list here. So let’s just record a list of the Shepherd’s outside activities. We might start by saying that he is the world’s champion holder of “keys to the city.” The keys are symbols of freedom and entitle the possessor to go anywhere and do anything (almost) that he pleases. None of them are rusty and if he chooses the Shepherd can go to 47 cities in his grand and glorious country and make himself at home.

During World War I, he began his long series of efforts for soldier entertainment. One terrific example of the type of entertainment that our shepherd put together is proved by photograph hanging his office. In that one show the players include: Houdini, Andrew Mack, Ray Goetz, Bert Green, DeWolf Hopper, Julius Tannen, Leon Errol, Raymond Hitchcock, Barney Bernard, Raymond Hubbell, Leo Carrillo, Frank Craven, Hedda Hopper, Alexandra Carlisle, Irene Franklin, Irene Bordoni, Lillian Russell, and the Dolly Sisters. We mention every one of the names of this unit because we doubt if any other soldier entrepreneur before or since ever put together a better bill.

About this time a little kiosk stood in Time Square and served as a distributing point for free milk given to poor children. It was one of Mrs. William Randolph Hearst’s pet charities. Through the Shepherd’s appeal to Mrs. Hearst, the kiosk was converted into the rendezvous for thousands of soldiers who were handed free tickets to all the theaters in town. Every manager in New York’s amusement world eagerly cooperated, to their everlasting credit.

That kiosk in Times Square was the forerunner of a greater organization which has been functioning since the start of the present war and is known everywhere around the world. Its headquarters are at 99 Park Avenue, and by the time this is published it’s very likely they will pass the 10 millionth free ticket given to an enlisted man of the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps. The Shepherd says, “I would rather have done this particular job than anything else in my life.”

Years ago John Golden set up a Loan Fund and now it is no secret that $16,000 is here at the Club to be used exclusively for loans for folks of the theater. He created and co-chaired dozens and dozens of charity events: The Army Emergency Relief, United Seamen’s Service, the Entertainment Department of the New York World’s Fair, co-organizer of the Stage Relief Fund, First Contributing Director of the American Theater Wing and Stage Door Canteen. Plus, John Golden had a friendship with six Presidents: Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson (with him he wrote a patriotic song), Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, and FDR. In fact, he holds a special medal with two words “Well Done” in the great Woodrow Wilson‘s hand. But the Shepherd caps them all with his recent donation of $100,000 which is to be applied for culture, relief, education, and encouragement of the theatre and folks of the theatre.