Clay Meredith Greene (12 March 1850-5 September 1933) was a prolific playwright from San Francisco. He was Shepherd of The Lambs for 11 terms as well as Boy and Director many times. He was elected to The Lambs in 1887.

Clay Meredith Greene (12 March 1850-5 September 1933) was a prolific playwright from San Francisco. He was Shepherd of The Lambs for 11 terms as well as Boy and Director many times. He was elected to The Lambs in 1887.

In 1887–when the club was only 13 years old–the routine of monthly club dinners grew tiresome. One winter evening, a group of actors was sitting around a table. Thomas Manning “waxed critical” and said, “I have grown aweary of these feasts of dearly-bought eloquence which cost so much and return so little.” Greene, the youngest, responded, “Then let us do this. Build for ourselves a mimic theatre in which our actors shall entertain the Fold, and at no cost to themselves save what they may buy from our store of food and wine.” On January 8, 1888, the Club held its first “gambol” in a makeshift theatre in the clubhouse at 34 West 26th Street. It was a smash.

Greene led the Club through perilous years and devoted the last 15 years of his career to it. At one time he loaned The Lambs about $35,000, without security, which would be about $700,000 today. He was named to the list of Immortal Lambs.

Greene was born in San Francisco on 12 March 1850, six months before California was admitted to the union. This was the Gold Rush era and Greene was exposed to all of it as a boy. His father, William Greene, was a pioneer and president of the first board of aldermen in the city. His mother was Annie Elizabeth Cotton Fisk, a pioneer from Rhode Island. Clay Greene’s parents claimed him “the first white male” born in San Francisco, a sobriquet that would follow him for the rest of his life. The family was prosperous and today Greene Street is named for William Greene. Young Clay Greene started writing plays and scripts in high school. In 1867, Greene’s parents sent him to Santa Clara College, where they hoped he would pursue studies in law or medicine. Instead, his college experience further solidified his interest in the theater. Upon his return to San Francisco in 1870, Greene worked as a newspaperman, writing for The Golden Era and its competitor The Argonaut. He was an early member of the San Francisco Bohemian Club. In 1878, Greene moved to New York to break into show business.

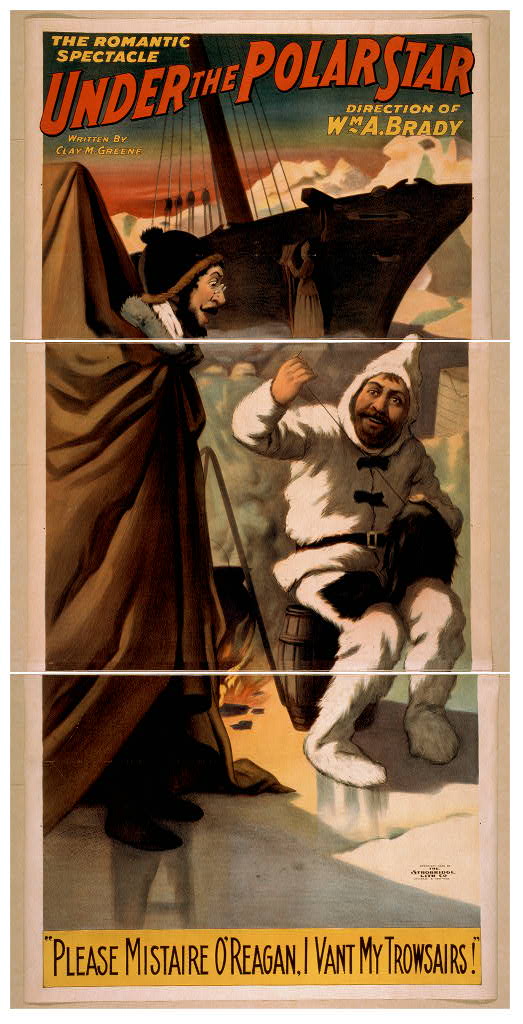

During a career of more than 40 years, he wrote and often acted in some 75 plays. Greene created dramas, comedies, and farces. He wrote the librettos for musical farces and operas. His Broadway credits include Under the Polar Star (1896), The Regatta Girl (1900), The Silver Slipper (1902), and Over a Welsh Rarebit (1903). When the motion picture industry was born his stories and scenarios were used for more than 50 movies. Among the silent pictures of Greene’s career are A Waif of the Desert (1913), The Klondike Bubble (1914), The College Widow (1915), and Millionaire Billie (1916). He also wrote the 12-part “Patsy” series starring Clarence Elmer that began with Patsy at School (1914) and culminated with Patsy, Married and Settled (1915).

In 1891 The Lambs were in trouble. The cost of operating the 26th Street clubhouse and many expensive (and unprofitable) festive dinners had accumulated the Club’s debts to the danger point. Shepherd Edmund M. Holland had just barely staved off bankruptcy. He declined to be nominated for a second term. Things were so bad–and bankruptcy became so certain–that some members resigned their membership because they feared they would be held personally liable for the Club’s debts. It was nearly impossible to convene a meeting of the Council to nominate a slate of officers because a quorum couldn’t be reached.

Lambs’ member Paul Arthur took it upon himself to nominate playwrights Clay M. Greene as Shepherd and Augustus Thomas as Boy. They were elected and re-elected through 1898 for a total of seven terms. Greene then served again from 1902-1906. Greene and Thomas were a uniquely vigorous and productive team. During these years, the Club would survive multiple financial panics, move its clubhouse three times, for the first time purchase its own building, nearly double its membership, revive the annual washings, and launch the first of its public or “Ladies” Gambols–lavish variety shows–and its first touring Gambol.

Greene found the Club’s finances in such perilous shape that he called weekly meetings to deal with the crisis. His plan to avoid disaster was simple and effective: increase membership and reduce expenses. To boost membership, the Club relaxed it’s restrictions on admitting non-theatrical members. In late 1891, The Lambs vacated its West 26th Street townhouse, subletting it for the duration of the lease. Lamb John Gilsey provided temporary quarters at his Gilsey House Hotel. The club could have done worse. Gilsey House was centrally located at the northern sector of the Rialto at the busy northeast corner of Broadway and West 29th Street, where trolley lines intersected. Its location in the busy portion of the uptown district with all the theaters near at hand was ideal. The eight-story edifice with it snow-white walls of Corinthian columns and balconies, topped with a three-story mansard roof and clock-tower, was an ornament in the city. Its spacious restaurant rivaled Delmonico’s and it boasted a cheerful gentleman’s café at the Broadway corner. The building is still standing.

With Greene as Shepherd, by the end of 1892, the Club was “freed from embarrassment.” Late that year the gypsy club moved to West 29th Street and in 1893 to 26 West 31st Street, where on January 7, 1894, it celebrated with the first Gambol in the new pasture. The Club troubles were by no means at an end. Panics during the period 1893-1895 caused a long period of great financial unrest. Ultimately it was Greene who saved the Club from extinction by paying the bills from his own personal bank account.

In 1897 The Lambs moved into their legendary clubhouse at 70 West 36 Street that is today’s Keens Steakhouse. At noon on April 13, 1897, Greene placed in a metal box Gambol programs, scripts, and other items into a marble block. This cornerstone was lowered in place. In May The Lambs entered their new Fold and remained there until 1905. By then they had outgrown the space with so many new members, and were building their biggest clubhouse of all on West 44th Street.

Many of his plays had very short runs, but in an age when a play could be a moneymaker with only a few weeks’ run, Greene became wealthy. He built an estate in Bayside, Queens, at the time growing as a fashionable theater colony where other Lambs resided at the time, or later, such as John Barrymore, John Golden, and W.C. Fields.

Greene revived the annual Wash, which had lapsed for several years, at his estate Los Olmos, in Bayside. As the carriages of revelers arrived, a group of Lambs costumed as Mexican vaqueros on horseback surrounded them, held them up, and conducted them to the Shepherd, who gave a welcome address in Spanish. In 1896 the theme for the wash was Arabian, in 1897 it was Bohemian. It was said with little exaggeration that Greene devoted the latter part of his career to the Club. “Old Reliable” was always ready to roll up his sleeves and get the job done. It is estimated that he wrote more than 100 sketches for Gambols and other club events.

Lambs’ member Robert Reid, among the foremost of American impressionists at the time, painted the luminous shepherd’s portrait of Greene that hangs in The Lambs’ clubhouse today. Since the Club at the time was hardly affluent, it is probable that Greene himself commissioned it. At first glance Reid’s portrait seems to depict a man who is expansive and relaxed, contradicting photographs that show him as intense, slender, handsome, and mustachioed with a wide Wagnerian temple and receding hairline. In old age Greene appears in photographs as wiry, dignified, and as proper as a banker. Moreover, some have observed that Greene’s eyes are the most realistic portion of the impressionistic canvas. They show impatience and seem to be saying to the artist, “Let’s get this over with.”

In 1873, Greene married Alice R. Wheeler, and their marriage lasted until her death in 1910. He surprised everyone by remarrying six months later. In 1911, he wed playwright Laura Hewett Robinson, a wealthy widow who brought three children from her former marriage: a son Arthur G. Robinson, and two daughters, Marion and Helen (later actress Helen Greene). Like his first wife, Robinson was a capable writer, and collaborated with him on various projects. Financial problems forced the sale of his Bayside estate, and, crowned with laurels, he returned home and retired in San Francisco.

Santa Clara College awarded him an honorary doctorate upon his return. In 1918 a hemorrhage blinded him. Greene made his final trip to New York to see his Brother Lambs in the Fold in 1930. The Club held a gala 80th birthday party in his honor with 80 candles blazing atop a cake. When he boarded the train to return West, he bid a final farewell to The Lambs. Three years later, in May 1933, Greene stumbled while walking near his home in San Francisco. He never fully recovered from a broken hip and passed away on September 5 with his wife and daughter at his bedside. Greene was 83. His New York Times obituary headline read, “Was First American Born in San Francisco–Shepherd of The Lambs Here 11 Times.”

Greene’s works are products of their time and are little remembered today. Basic theatre reference works no longer include his name; his plays are not in their listings. However, when The Lambs established a scroll of Immortal Lambs–deceased members who, by the benevolence or devotion to club service, made it possible for the club to survive–Clay M. Greene‘s name was the first to be recorded.

Adapted in 2022 from the research and writing of Lambs’ historian Lewis J. Hardee, Jr. Additional research by librarian Kevin C. Fitzpatrick