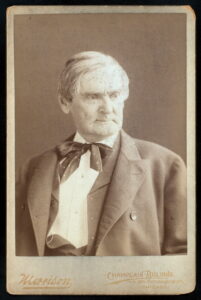

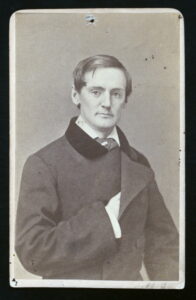

Joseph Jefferson III (1829-1905) known as Joe Jefferson was a legendary stage actor of the 19th century who built his entire career on a single role: Portraying Washington Irving’s character Rip Van Winkle. He was elected to The Lambs in 1890 as a Professional member. Of his nine children, five sons were elected to The Lambs. Jefferson was friends with scores of Lambs over the years, including shepherds Lester Wallack and Edmund Holland. He was given honorary life membership in The Lambs in 1900.

Joseph Jefferson III (1829-1905) known as Joe Jefferson was a legendary stage actor of the 19th century who built his entire career on a single role: Portraying Washington Irving’s character Rip Van Winkle. He was elected to The Lambs in 1890 as a Professional member. Of his nine children, five sons were elected to The Lambs. Jefferson was friends with scores of Lambs over the years, including shepherds Lester Wallack and Edmund Holland. He was given honorary life membership in The Lambs in 1900.

As the third actor of this name in a family of actors and managers, Jefferson completely eclipsed his forebears. He made his stage debut at the age of three in August von Kotzebue’s “Pizarro,” and, after years of struggle as a traveling actor and manager, Jefferson achieved his first important success in Tom Taylor’s “Our American Cousin” (1858), a play that was the turning point in his career. Other plays acted by Jefferson in those years included Dion Boucicault’s Octoroon (1859). His Bob Acres in The Rivals by Richard Sheridan, although very successful, was more Jefferson’s creation than the author’s.

The friend of many leading figures in politics, art, and literature, Jefferson brought dignity to the stage. Both Yale and Harvard bestowed honorary master’s degrees on a man who never went to high school. Jefferson’s Autobiography (1890) is written with spirit and humor. The Lambs counts a first edition of the book in the Club library as a treasure.

He was born into show business on February 20, 1829, in Philadelphia. He was the third actor of this name in a family of actors and managers. His father, Joseph Jefferson II (1804-1842), was an actor and scenic designer. His actress mother, Cornelia Frances Thomas (1796-1848) had been a widow who acted professionally as “Mrs. Burke.” His parents raised him and his siblings for the stage. Naturally, he went onstage whenever a baby or small child was needed.

When he was four years old, the boy was carried out at the Washington Theatre in a bag by Thomas D. Rice, in a minstrel show. He put the child in black face and a dress with Rice performing his well-known character “Jim Crow” and young Joseph as “Little Joe.” When he was about eight, Little Joe performed as a pirate at the Franklin Theatre in New York with his parents. Around 1838 his parents moved Joseph, his half brother Charles Burke, and his sister, Cornelia, to Chicago to take up residence in the Chicago Theatre, the first professional acting company in the growing city.

Two aunts of Joseph Jefferson III were members of the first professional theater company to perform in Chicago. They arrived in 1837, the same year as the incorporation of the city. Joe aged 9, appeared with his actor parents one year later. The attorney representing his father’s acting company for licenses and other matters was Abraham Lincoln.

His father died when he was 13, and young Jefferson continued acting to support the family. Both Jefferson and his half-brother performed continuously, and the entire family toured towns big and small. Traveling from town to town via rail, Jefferson performed across the Northeast, Midwest, and South.

During the 1840s and in the era leading up to the American Civil War, Jefferson appeared in front of any paying audience, from rooms in hotels to small community stages. During the Mexican War he went to Texas to entertain any paying customers in frontier towns. In 1849 he was one of the seven founding members of the Actors’ Order of Friendship, a benevolent society founded in Philadelphia. He also served as the organization’s first Secretary, a move that would give him insight into the treatment of actors in the era before theatrical unions and social clubs. He was 31 years old when the Civil War began. By then he had established himself in New York, which would help as he prepared to begin the next and greatest phase of his long stage career.

During the 1840s and in the era leading up to the American Civil War, Jefferson appeared in front of any paying audience, from rooms in hotels to small community stages. During the Mexican War he went to Texas to entertain any paying customers in frontier towns. In 1849 he was one of the seven founding members of the Actors’ Order of Friendship, a benevolent society founded in Philadelphia. He also served as the organization’s first Secretary, a move that would give him insight into the treatment of actors in the era before theatrical unions and social clubs. He was 31 years old when the Civil War began. By then he had established himself in New York, which would help as he prepared to begin the next and greatest phase of his long stage career.

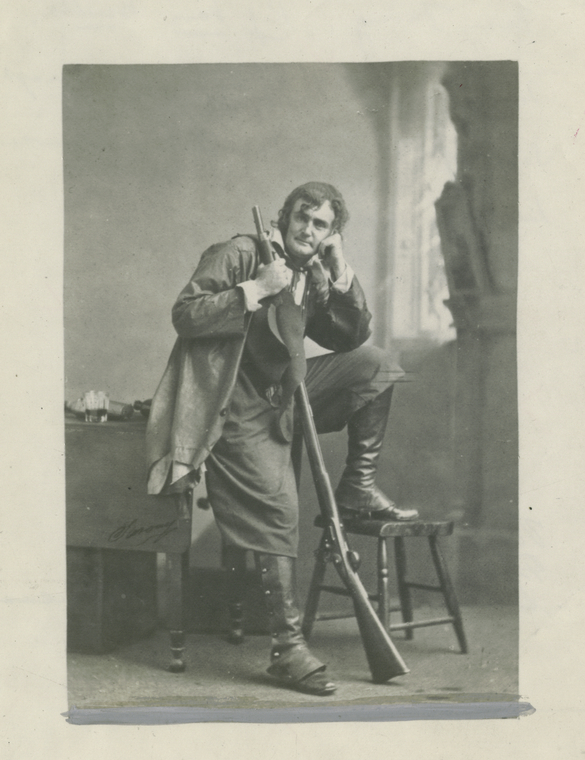

In 1859 Jefferson adapted the stories of Washington Irving’s story of Rip Van Winkle, drawing from older plays. He acted it with success in Washington, D.C., with Sophie Gimber Kuhn playing the role of Lowenna. Written in 1819, and set in pre-Revolutionary New York in the Catskill Mountains, Rip Van Winkle lives a life of ease – much to the chagrin of his wife, Dame Van Winkle. Rip’s passions include wandering through the Catskills and old-growth forests, being idle and enjoying life. One day, Rip wanders off into the woods to escape his nagging wife. Hearing thunder, he unwittingly follows the ghosts of Henry Hudson’s men deep into the forest. As the men play nine-pins, Rip imbibes a “magic potion” – quietly falling into a deep sleep. He wakes up 20 years later, his beard grown long and white. Rip makes his way back into the village and discovers that the American Revolution has taken place. He is no longer recognizable, nor does he know any of the townspeople who greet him. It is a classic folktale, and hailed as an American legend.

Jefferson took that play on the road, first to California, and then onto Australia, where he refined it. With his young family, he traveled throughout the Civil War years. He was preparing to sail home when word of President Lincoln’s assassination reached him. This shook him to his core; he was a generally fun-loving and easy-going personality. The news “jolted his father and sent him into uncharacteristic despondency,” his son, Charles, recalled. He knew Lincoln through his father and the Booth family from the stage. Jefferson did not want to return to New York yet. He set a course for London.

While in England he revised Rip Van Winkle with the help of Irish playwright Dion Boucicault, a future charter member of The Lambs. With his help, the show was a smash success in London. Opening night was on September 5, 1865, at the Adelphi Theatre. Jefferson portrayed what would become one of the most celebrated characters of the 19th-century stage. It ran for more than 170 nights, a healthy box office in the era, which boosted his spirits and sent him back to the United States on a wave of critical success.

While in England he revised Rip Van Winkle with the help of Irish playwright Dion Boucicault, a future charter member of The Lambs. With his help, the show was a smash success in London. Opening night was on September 5, 1865, at the Adelphi Theatre. Jefferson portrayed what would become one of the most celebrated characters of the 19th-century stage. It ran for more than 170 nights, a healthy box office in the era, which boosted his spirits and sent him back to the United States on a wave of critical success.

Jefferson returned to New York in August 1866. He continued acting in Rip Van Winkle for 40 years, and performed very little else for the rest of his life.

Jefferson was married twice: in 1848 to English actress Margaret Clements Lockyer (1832–1861). They had five children who survived: Charles Burke Jefferson, Thomas Lockyer Jefferson, Margaret Jane Jefferson, Frances Florence Jefferson, and Joseph Jefferson, Jr. Charles and Thomas joined The Lambs. After Jefferson returned to the United States after the end of the Civil War, he remarried in 1867 to Sarah Warren (1849-1921). They had four children: Josephine Duff Jefferson, Joseph Warren Jefferson, William Winter Jefferson, and Frank Pierce Jefferson. Joseph, William, and Frank joined The Lambs.

He launched annual tours of “Rip Van Winkle” across the country, and was richly rewarded with accolades and honors. His reputation rose in the Gilded Age Era at the same time that acting was rising as a respectable profession. In 1874 his old friends formed The Lambs, and he was elected to join them in 1890 as a Lifetime member. The Players was founded in 1888 and upon the death of founder Edwin Booth in 1893, Jefferson was made the club’s honorary president. In 2013 The Players nearly lost their oil portrait of Jefferson by John Singer Sargent when it was used as collateral on a multi-million dollar loan to save their clubhouse; The Players sold two other Sargent paintings it had owned and put up copies. The Lambs Foundation owns a rare print of Jefferson by Lamb Howard Chandler Christy in his Rip costume.

Jefferson owned multiple properties. His summer residence was in Bourne, Massachusetts, his beloved “Crow’s Nest” estate on Buzzards Bay. Among the visitors were President Grover Cleveland and fellow Lambs John and Lionel Barrymore. For winter vacations, in 1869, Jefferson bought land on Lake Peigneur in New Iberia, Louisiana, 150 miles west of New Orleans. He used it for entertaining, hunting, and fishing with friends. Jefferson built a large plantation house that today is the Joseph Jefferson House, an event space and house museum. The peninsula is called Jefferson Island and the streets are named for Rip Van Winkle.

By the end of the century, Jefferson was still selling tickets to see his performances in “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Rivals.” He toured with fellow Lambs Wilton Lackaye and Otis Skinner to boost the box office. In 1898-1899, unable to go onstage, one of his sons,Thomas L. Jefferson, subbed for his father and Charles B. Jefferson managed the tour.

Around 1895, Jefferson bought a villa in Palm Beach, Florida, he named The Reef. He spent his days painting sunsets and seeing his friend, railroad tycoon Henry Flagler. Jefferson had a valet who pushed him around Palm Beach in a wicker wheelchair, greeting the locals. Jefferson died on April 23, 1905, at his home in Palm Beach. He was 76 years old. Newspapers across the country and in Europe printed laudatory tributes. As the Palm Beach Post reported more than 100 years later:

“…schools and shops closed, flags flew at half-mast, and his life’s work was proclaimed from Palm Beach’s Town Hall to the White House. More than 100 of Jefferson’s fellow Masons accompanied the family to the nearby train stop at The Breakers where they were met by railway car No. 90, Henry Flagler’s private car. When the funeral cortege left The Breakers and crossed the railroad bridge, Bethesda-by-the-Sea’s church bells were in concert with West Palm’s extended fire alarm bells.”

Joseph Jefferson is interred in the family plot in Bay View Cemetery in Sandwich, Massachusetts. His gravestone has a carved profile of the actor, and the reverse has lines from his autobiography of Rip Van Winkle’s soliloquy:

“And yet we are but tenants. Let us assure ourselves of this, and then it will not be so hard to make room for the new administration, for shortly the great Landlord will give us notice that our lease has expired.”

The missing cup: In 2011 Sotheby’s sold The Joseph Jefferson Cup: A massive American silver presentation cup, modeled by W. Clark Noble, cast by Gorham mfg. Co., Providence, RI, 1895-96. This was the property of The Lambs, and how it left the Clubhouse remains a mystery.

Additional research and genealogy prepared by Shepherd Kevin C. Fitzpatrick, 2023.